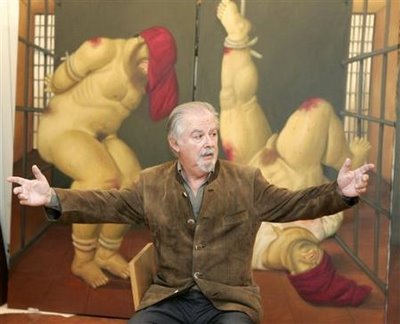

Newsflash! If you live in Southern California you will be able to see this amazing artwork. January 21 - April 15, 2007 at the

Pasadena Museum of Art! The exhibit will then travel to Utah and Washington DC. I'll get more information for you about those shows.

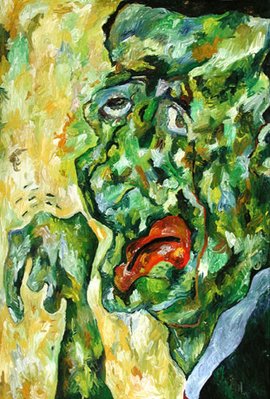

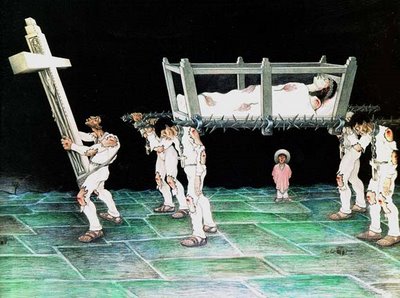

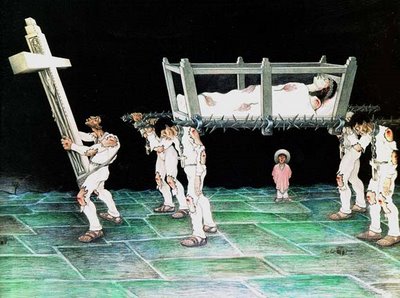

Elevator © Irving Norman 1946

Elevator © Irving Norman 1946(Click on image for larger view).

All images in this series are presented with Hela Norman's permission.

This is the final installment of the series on Irving Norman. I was lucky enough to see the exhibit three times (something I've never done at any art show before) at the Crocker Museum in Sacramento. If you missed the exhibit you can still see Norman's work via

virtual tour or purchase the beautiful 220 page oversize color

catalog.

Here is the final excerpt from the 1975 interview artist

Roberta Loach did with Irving Norman. I hope you've enjoyed this unique view into the creative motivations of this visionary artist. You'll find the previous segments of this series here:

Interview Part 1Interview Part 2Introducing Irving Norman Part 1Introducing Irving Norman Part 2Roberta Loach: How important to you is design and color and what do these elements have to do with what you are trying to say?

Irving Norman: Everything. I have learned design and daring in design, especially from modern artists such as the Futurists, a very underestimated group of artists.

RL: What are your feelings about non-objective art? And has it influenced you in any way?

IN: I feel that non-objective work is at the top of its significance, and has been for the last fifty years. My work shows my reaction to it. You see, my heroes are Sartre and Camus. I think of them as philosophers representing their thinking of France and the West nations which have fulfilled their mission in terms of world power and they see the fulfillment of this power as illogical, senseless and absurd in terms of the whole of human existence. So that is the thinking that leads to abstraction and at the same time to the concrete. Sartre as a political activist and existential thinker combines the two. This is what some people call the universal in my work...the combination of the concrete and the abstract.

RL: I can see the concrete in your work such as in the buildings, subways, total composition, placement of the figures...but where's the abstract?

IN: Mostly in my preoccupation with death.

RL: You're speaking philosophically of course, but your treatment of space helps carry out this point pictorially.

IN: Yes. There is no answer to this problem of existence. It's like the theatre of the absurd. It all seems to come to a senseless head when a civilization reaches its fulfillment and has nowhere to go. In the meantime, we have to react to our own time like Thomas Wolfe says.

RL: How do you mean?

IN: Wolfe, as you might know, gave detailed descriptions of life in every aspect in the big American cities. His publisher objected, suggesting that he bother himself only with the ultimate. The publisher said that life is and always has been full of problems and always will be. Wolfe said, "No. You may be right, but everyone has to help clarify the problems of his time." If he can't solve it, he can at least analyze and clarify it. That's what he did and that's what I try to do.

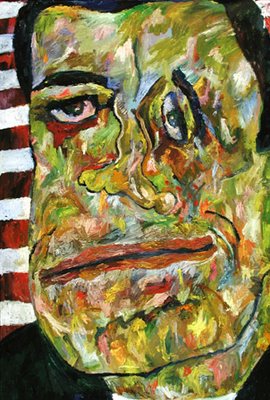

From Work © Irving Norman 1943

From Work © Irving Norman 1943(Click on image for larger view).

All images in this series are presented with Hela Norman's permission.

RL: How do you react to people who criticize you for only presenting the problems and not offering any solutions?

IN: Well for me the burden of analyzing the truth as it is is so big that I can't visualize the solutions. The Martyrs for example, shows the power of protest and self sacrifice which are methods of solving certain problems.

RL: One last question...how do you feel about your own work now? Are you pleased with the success you are having? Does it make any difference to you?

IN: No difference at all. In fact I'm worried about it.

RL: Why are you worried?

IN: It's a distraction...I never thought of it. Once in a while I had an exhibit and people came and bought a few things and it enabled me to take a trip and raise my spirits...but otherwise I haven't paid attention to it. As I said earlier, I'm just curious about everything and I try to give expression to it.

RL: Do you think you would have continued to work had you not had any chance to show or sell or reach appreciative audiences?

IN: I think so...it's discouraging. You have to fight it off. It draws a bit on your energy, but it's all part of this world. You can't get out of your own skin. I just want to react to life through my work.

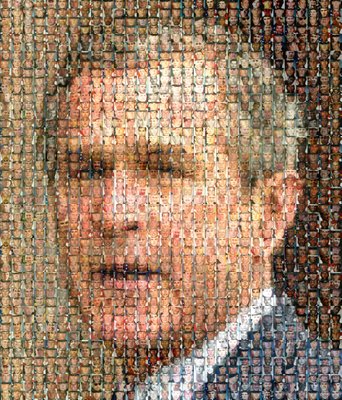

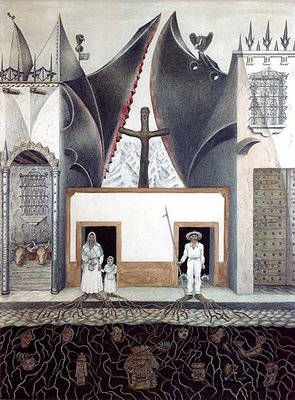

Mexican Procession © Irving Norman 1946

Mexican Procession © Irving Norman 1946(Click on image for larger view).

All images in this series are presented with Hela Norman's permission.

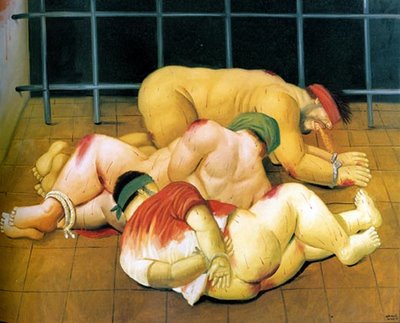

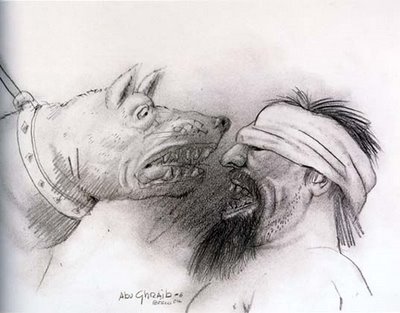

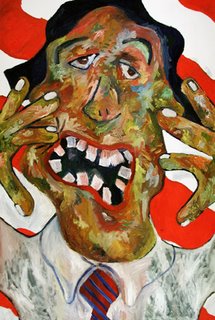

And now commentary from interviewer Roberta Loach

As the reader may well have deduced from this conversation, Irving Norman is out of step with the trendy art of our time. He is unfashionable...a devout humanist, unashamedly concerned with the plight of his fellow man. His work also reveals his concern with the ubiquitous existential dilemma of life that seems to be the lot of all human kind who stop long enough to think about it. Irving Norman is bold, courageous and committed and like all who dare to show such feelings, he is inevitably accused of being morose, unhappy, angry and humorless. He is none of the above. He is a contented man on good terms with life and himself, doing the work he feels he must. He is a mind alive, fascinated, dismayed, aware and above all, tuned in to the realities of life and unafraid to look at and ponder the ugly social and political truths of today that no sane person could deny. Like Thomas Wolfe, he seeks to clarify and analyze the problems of his time, using his powerful gift as an artist to do so. His very act of creation is an affirmation of his optimism about life, though, as Camus would say, "not a forced optimism which is the worst of luxuries and the most ridiculous of lies."

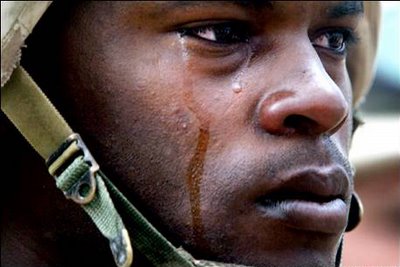

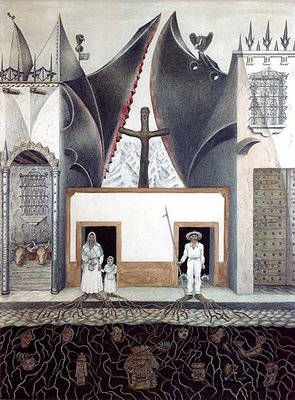

Roots © Irving Norman 1947

Roots © Irving Norman 1947(Click on image for larger view).

All images in this series are presented with Hela Norman's permission.

Irving Norman is the epitome of the figurative artist who has something to say, and because he has chosen his agonizingly tormented, distorted figures to express the depths of his feelings, he is looked upon by some of the elitist museum crowd as being too literal and just possibly too controversial for some of their more substantial patrons. How ironic that the very reasons his work is often shunned are the reasons which serve as a perpetual spur to his creative impetus. How can he, possessed of a greater ability than most, turn his back on reality and fail to record it in his "literal" work? In essence, Camus asks the same question: "How can art get along without the real and how could art be subservient to it: The artist chooses his object as much as he is chosen by it. Art, in a sense is a revolt against everything fleeting and unfinished in the world. Consequently its only aim is to give another form to (a) reality that is nevertheless forced to preserve as the source of its emotion. In this regard we are all realistic and no one is." Norman can't get away from the belief that art and life are inextricably tied up with each other. He is a good example of the artist who can neither turn his back on his time nor lose himself in it. He is a unique artist who responds in his own way to his own time with the totality of his being. It seems fitting to close with Camus who understood the true artist so well: "Art advances between two chasms, which are frivolity and propaganda. On the ridge where the great artist moves forward, every step is an adventure, an extreme risk. In that risk, however, and only there lies the freedom of art." As Irving Norman knows all to well. - Roberta Loach 1975.

Please respect the work of the artists you see here and be sure to credit them when you share their artwork with others. To share your opinion on this or any other post, please click the word "COMMENTS" below.